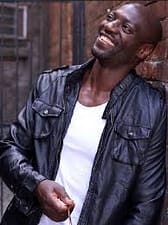

'I didn't Want to Be Black. So I Joined the Skinheads…' – Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje

The name Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje is not one that slips easily off the tongue but it’s worth mastering because we’re likely to be hearing a lot more of it in the future. Followers of the wilfully perplexing American fantasy series Lost may recall its owner as Mr Eko, the former drug lord turned fake priest who was killed by the Man in Black, otherwise known as the Monster. Or perhaps not.

Some will know him as Simon Adebisi, the intimidating African convict in the cult HBO prison series Oz; others may recognise his contributions to films such as Congo and The Bourne Identity; and no doubt his role as an American spy in the forthcoming BBC-HBO series Hunted will further raise his profile. But it may well be as the screenwriter and film director of his own life story that Akinnuoye-Agbaje becomes a name to remember.

Armed with an Annenberg Film Fellowship grant, Akinnuoye-Agbaje has been working on the film for several years, developing the story at the Sundance Institute Directors and Screenwriters Labs. A read-through of the script by a cast including David Harewood and Marc Warren became one of the most talked about events at the recent Sundance London festival.

Entitled Farming, it refers to the practice of handing out children to informal fostering that many Nigerian parents followed in 1960s and 1970s Britain. Akinnuoye-Agbaje was one such case. In 1967, when he was six weeks old, his parents – a Nigerian couple studying in London – gave him to a white working-class couple in Tilbury, then a fiercely insular dockside community. Six months later, the Tilbury dockers led strikes in support of Enoch Powell.

Akinnuoye-Agbaje hopes to start shooting the film later this year. It’s a neo-Dickensian tale of hardship, abandonment and solidarity, a kind of black Oliver Twist for the postwar immigration era. Now a powerfully built 44-year-old man, he recalls the vulnerability of his childhood with such a generous mixture of humour and understanding that it’s difficult to keep in mind that he came through circumstances that would have crushed the strongest of spirits.

At times his foster parents had 10 or more African children living with them, including Akinnuoye-Agbaje’s two sisters. “It was a strange relationship,” he recalls of his feelings for his foster parents. “It was one of love because that’s all that I knew, and that’s what love is: you accept people for what they are. If I’m honest, it was very tough. My father was a lorry driver, very rarely at home. The house was run by my mother, and because there were 10 or so kids, there was no time for individual attention. It was about survival. It was about where the next meal was coming from. We had to go out and nick things to get it. So there wasn’t any love in the sense of hugs or anything like that: there was just no room for it. The only haven I had was sleeping behind the sofa in the corner of the room – that was where I could get some kind of peace.”

If it was crowded and chaotic within the home, outside the young boy was in constant danger of physical attack from local kids who, encouraged by their parents, nurtured a violent fear of blacks. He learned to feel the same way himself, running away from the black sailors who occasionally visited the docks from far-off locations.

“I just remember being petrified,” he says. “It was as if they were the bogey man to us. Fish and chips and corned beef, that’s what I knew. Do you know what I mean?”

As far as the chips and corned beef go, only too well. But the rest is less easy to imagine. Such was his eagerness to fit in that, although his skin clearly told another tale, he thought of himself as white. And if his sense of self wasn’t already damaged enough, he knew nothing of his African parents until one day, when he was eight, they turned up out of the blue and took him back to Nigeria.

“It felt like a kidnap,” he says, “and it rendered me mute for about nine months. I couldn’t speak the language, and if I spoke English I was abused for it. It was quite a culture shock: brutal. I was so traumatised and afraid that I stopped speaking and my [birth] parents thought there was something wrong with me, thought I was possessed. They tried various indigenous ways to deal with it, and when they didn’t work they sent me home, back to Tilbury, but kept my sisters there.”

You wonder where the authorities were while young Adewale was being treated like some human missile, fired back and forth between continents. If his natural parents were not prepared to bring him up, it didn’t help that his foster parents were ill-prepared. “There was a lot of ignorance in the family,” he says as a neutral observation rather than a complaint. “I don’t think they were racist; they were ignorant. They didn’t know that we had to put cream on our skin because the skin is for warmer climates and it turns ashy in the cold. They didn’t know they had to put cream in our hair. They didn’t know we had a different smell from Caucasians and we were persecuted because of it. They were just raising us as they would a white kid, but there were differences, marked differences, and I learned about that as I started to grow up.”

This was a different time, of course, when social services maintained a more remote involvement in childcare arrangements and there was much less appreciation of cultural distinctions. In the 1980s there came an identity backlash. Fostering, and especially adoption, were made far more stringent in relation to children from minority backgrounds. A policy of cultural and ethnic determinism was instituted that left many children, who might otherwise have found loving homes, in care because no suitable racial match could be found.

Identity and adoption are complex issues with no easy fit-all answers. But then Akinnuoye-Agbaje doesn’t have any easy answers to offer. “It’s a significant question: should black people only adopt black children, and white people white children? My film doesn’t judge in that sense. It makes you aware of the possible dangers but if there’s anything to be gleaned from this story it’s that if one is from a certain culture and then fosters someone from another culture, one should really take the time to learn about that other culture because there will come a point when the child will need to know about whence it came.”

As relieved as young Adewale was to return to Tilbury as a nine-year-old, he had also learned something about his background, and it disturbed him. For the first time he was aware of being on the outside and looking in, and realising that he was not the same as his foster parents, despite their insistence that he was. “Now I had a reference point and that really highlighted my cultural identity crisis,” he says. “I wanted to assimilate and go back to the abnormal normality I knew. I wanted to wash off the experience of Africa but obviously I couldn’t because that’s who I was. As much as I wanted to deny it, it was plaguing me, and I was reminded by the images coming through the TV, people on the streets and in the end my family in the house.”

The more he tried to blend in, the more he was rejected. After a year in Africa his skin was darker, which made him yet more conspicuous among the white population. Reluctant to go out, he was issued with an ultimatum by his foster father: either he fight in the street or he would have to fight in the house. With little choice, he learned to defend himself and also to attack others. As he became a teenager he grew into a well-built young man with a reputation for violence.

“It was a time of standing up and standing your ground or running, and there wasn’t anywhere to run in Tilbury. The local skinhead gang really ran the streets. They made my life – and anyone’s who was a shade darker than pale – a misery.”

There’s a natural human tendency to dramatise our backgrounds, embellish challenges and exaggerate difficulties, and actors are certainly not immune to the impulse. But there’s no bravado or sentimentality in Akinnuoye-Agbaje’s manner. Instead he displays a passionate and perhaps cathartic desire to explain, not least because what took place next requires some explanation.

He became a skinhead.

He didn’t just adopt the haircut and clothes but the racist attitudes too. He fought alongside his new skinhead comrades, who treated him at first like some brutalised pet to be unleashed in battle. “I was like a little dog that followed them around,” he says.

“When a child wants to be accepted,” he explains, “he’ll do anything. And if it means you’re getting a certain amount of notoriety from a fight, that’s what you’ll do. If all you’ve known is racism, abuse and persecution, then all of a sudden you’re getting some recognition, that’s your new drug. That’s what you want. By the time I was 16 I was someone to reckon with. I was so eager to repudiate any connection with any immigrant race I would go above and beyond. I was desperate to belong to something. That was my drive as a teenager.”

He became a bully and a thief and seemed set to pursue a life of crime and dysfunctionality. Unable to cope and worried that he would become a disruptive influence on the other children in her care, his foster mother got in touch with his birth parents. At 16 he was once again removed from Tilbury, this time not to Africa but to a boarding school in Surrey, paid for by his parents – his father was a qualified barrister with a lucrative practice in Nigeria.

The relationship with his birth parents had not improved in the intervening years. He was a street kid who spoke a raw cockney dialect, and they were two professionals, unwilling to acknowledge responsibility for what they had inflicted on their child.

“It was hell on earth,” he says, shaking his head at the memory. “It was really the most bizarre thing. I was like, ‘Eff off, you wog’. They were total strangers to me, and there was no marrying the two worlds of Tilbury and Africa. No way.”

Such was the disorienting shock of boarding school, with its unsettling silence and atmosphere of academic expectation, that the overwhelmed teenager, now confronted with his own self-hatred, attempted suicide.

He couldn’t turn back but didn’t know how to go forward. He found it hard to concentrate and he struggled to understand what he was being taught. But gradually, with the help of a girlfriend and a fellow student, he began to accept his heritage, and he also learned how to study, going on to gain a law degree from King’s College, London.

He was and remains grateful to his birth parents for eventually providing an education but he never forged a close relationship with them. His birth father is now dead, as are his two foster parents, whom he thinks of as his real parents. “They were the ones who raised me, for good and bad,” he says. He stayed close to them right up until their deaths.

While at university he worked in a clothes shop where, in turn, he was introduced to modelling. That took him around the world and eventually to Hollywood, and the cast of the film Congo. The instant he started acting, he knew it was his vocation. “I realised that the sum total of my life added up to this: my rough upbringing, because when they said ‘Action!’, I had plenty; and the analytical focus and determination of legal study – you need all of that to be an actor,” he says, breaking into a broad and knowing grin.

“And obviously my natural charisma and showy self, because you’ve got to be star inside.”

Akinnuoye-Agbaje is indeed a star inside and out, but the hardest and most triumphant role he’ll ever play is the one he was handed by his parents as a baby of just six weeks.

Leave a Reply